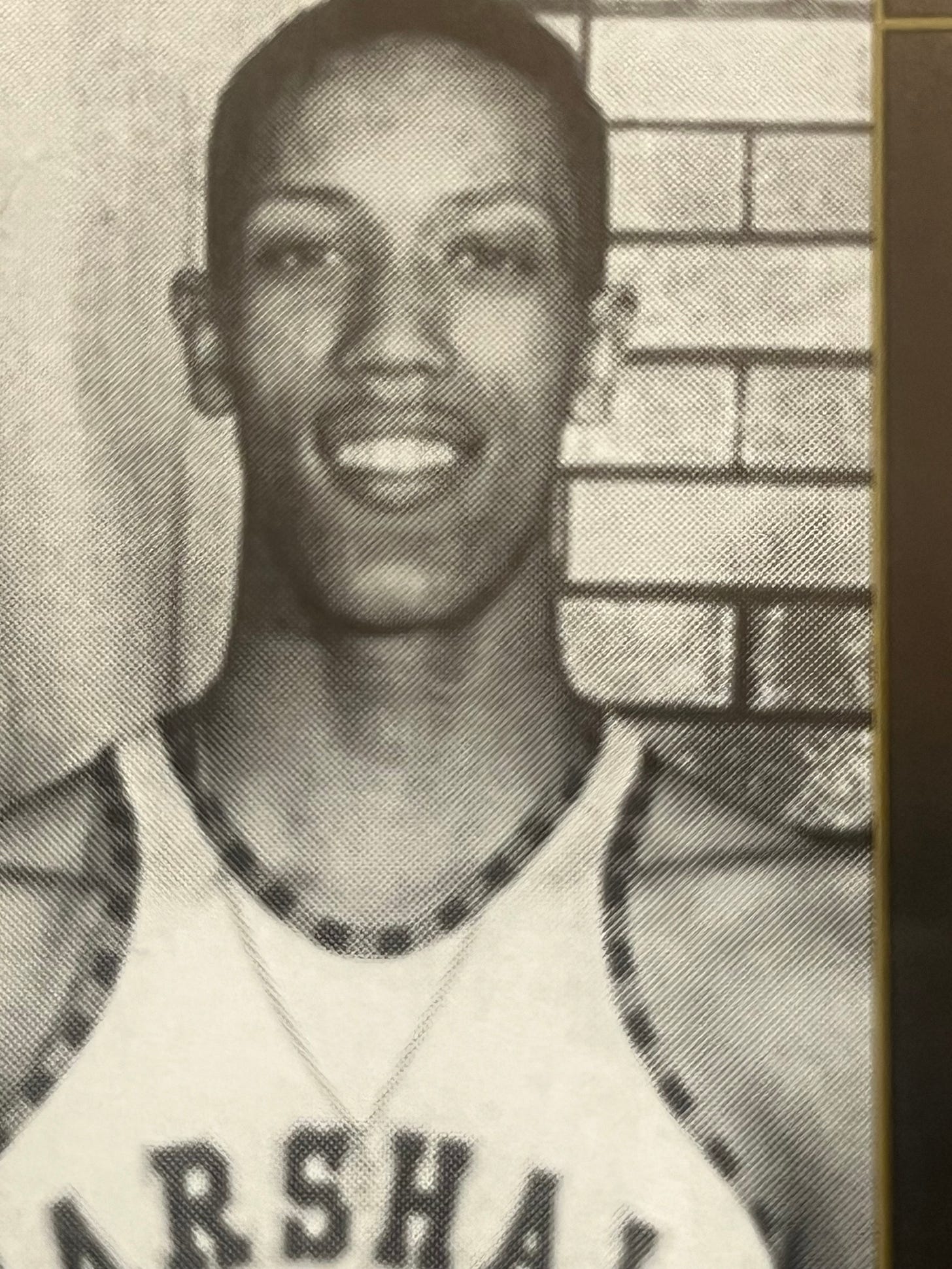

Remembrances: “Big George” Wilson’s Achievements Stand Tall with the Legends of Illinois Basketball

Leader of Marshall's Public League Title Breakthrough, NCAA and Olympic Champion, NBA Player Passed Away Saturday at 81

There is no disputing George Wilson’s status as one of the most historically significant basketball players from the city of Chicago and state of Illinois.

Feel free to debate whether Wilson’s game of 60-plus years ago would translate to success today. The grainy, soundless black-and-white video available from Marshall’s second state title victory in 1960 lends credence that Wilson would hold his own.

Only one player in boys state history can exceed what Wilson, known as “Big George,” accomplished as a two-time state champion at Marshall, NCAA champion at Cincinnati and 1964 Olympic Gold Medal winner before embarking on a seven-year NBA career. Two-time Thornridge state champion Quinn Buckner added an NBA championship with the Celtics to the ones he won in 1976 with Indiana University and the U.S. Olympic team.

And it’s why Wilson, who passed away Saturday at 81, should be mentioned more often among the great players to go from Chicago to success at higher levels.

“Wilson at 6-8 controlled the game inside and out as the first modern small forward forerunner of the Magic Johnson-Larry Bird type,” said legendary IHSA and national broadcaster Tom Kelly on “March Madness: The Illinois High School Basketball Tournament Video.”

“Everyone knew George was going to be something special,” Wilson’s Marshall teammate Jim Pitts told legendary prep writer Taylor Bell in his book, “Sweet Charlie, Dike, Cazzie and Bobby Joe: High School Basketball in Illinois.” “He could build a great team and inspire confidence. He was a young Bill Russell. He could start a fast break with a rebound and end it with a dunk. He showed all we needed was a standard of excellence and we could do anything.”

What Wilson did as a three-time high school All-American helped Chicago finally break through into the winner’s circle in a 50-year-old IHSA state tournament which had been dominated by southern Illinois schools. The famed DuSable Panthers were the first city team to make the state championship game in 1954 and suffered a controversial loss to Mount Vernon.

Wilson moved to Chicago from Meridian, Mississippi when he was 7. As a sophomore, Kelly said he was, “already the dominant player in Chicago’s Public League. Wilson had a smooth hook shot and was one of the first players to dunk in a game.”

Marshall followed DuSable’s path to Champaign’s Huff Gym in 1958 and beat Rock Falls 70-64 in the title game to finish 31-0. The Commandos were honored with a ticker-tape parade in downtown Chicago and met with Mayor Richard J. Daley and the City Council. Wilson averaged 21.5 points in four tourney games and in a 63-43 supersectional win over Elgin, he outscored future NBA All-Star Flynn Robinson 26-20 and held 6-11 George Clark scoreless on 4 shots.

“We became part of history,” Wilson said in the March Madness video, “so no matter what happened in Illinois high school basketball we were the first and that was the way we felt.”

Most prep experts pegged Marshall and Wilson to repeat in 1959 but they were derailed in a controversial 1-point supersectional loss to Waukegan where Wilson was hampered by early foul trouble.

“The most disappointing experience of my life, worse than losing to Loyola (for the 1963 NCAA title),” Wilson told Bell. “I’m still bitter. But you can’t go back. I learned from that. We didn’t cry. It just motivated us for 1960.”

Did it ever. Marshall went 31-2 and got back to Champaign with a 71-55 win against an Elgin team with future Elk Grove teacher and coach Britt Farroh. Head coach Spin Salario told Bell that Wilson could have scored 40 a game if he geared his offense to him. But it wasn’t necessary and Wilson scored 17 in a 79-55 title-game win over Bridgeport, a school of less than 400 students in southern Illinois near the Indiana border.

“He made all the difference in the world,” Salario said in the March Madness video. “You get a kid 6-9 that could get the rebounds for you, throw the ball out to a guard and then lead the fast break (Salario laughed), he was something else.

“We would move him outside. When we were pressed I’d have George come up and help break the press or even bring the ball down. He did so many things and could do them well.”

That’s evident from watching No. 33 in the title-game video. Wilson had at least 6 blocked shots and kept all of them in play. He took rebounds and fired on-target outlet passes or used his ball-handling skills to push the ball upcourt. He hit the open teammate out of the low post, showcased a midrange game in the lane and hit a pullup jumper from around 20 feet on a fastbreak.

Marshall went 87-6 in Wilson’s final three seasons and he was an easy pick for the “100 Legends of IHSA Boys Basketball Tournament” for its 100th anniversary in 2007.

“He had the talent and speed. He was faster than any big man,” said 1958 teammate M.C. Thompson in Bell’s book. “He was a fighter. He would always take a risk.”

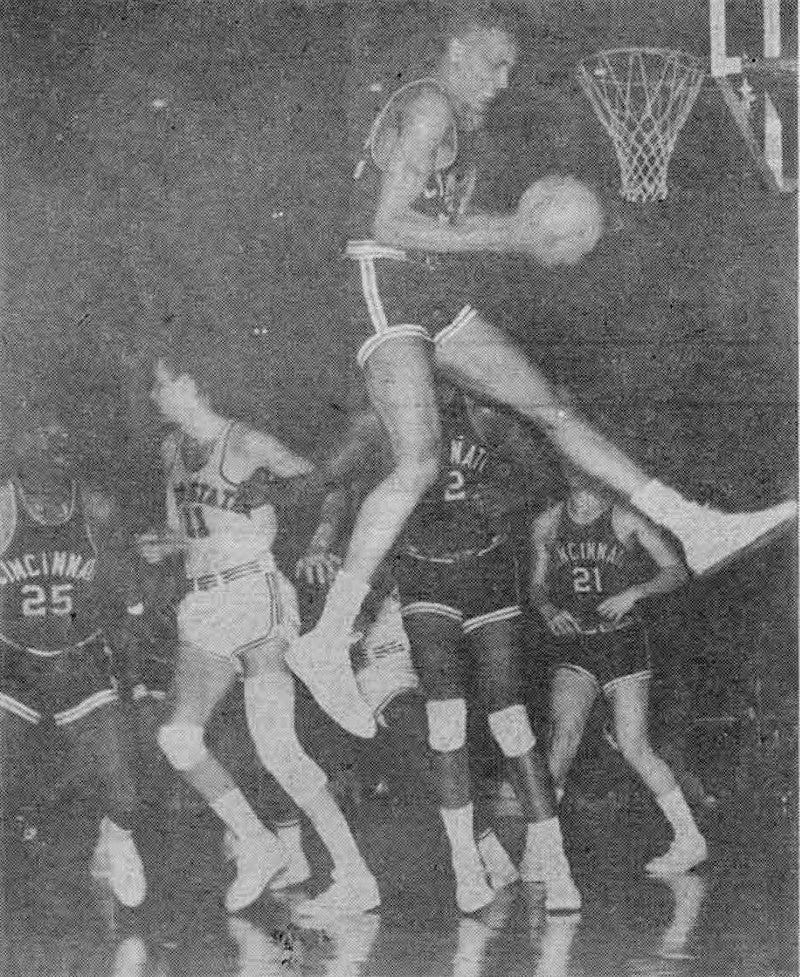

Wilson signed with Cincinnati and Illinois but opted to head out of state after meeting the legendary Oscar Robertson on a recruiting visit. Wilson didn’t play on the Bearcats’ first NCAA title team in 1961 because freshmen were ineligible to play in those days. But midway through his sophomore year he broke into the starting lineup, averaged 9.2 points and 8 rebounds a game and had 6 points and 11 rebounds as the Bearcats repeated as champions by beating Ohio State.

He broke out as a junior to average 15 points and 11.2 rebounds a game en route to second-team All-America honors and it also looked like Wilson and the Bearcats would win a third consecutive title in 1963. But they couldn’t hold a 15-point second-half lead and Loyola won at the overtime buzzer. Wilson’s 10 points and 13 rebounds were his fourth double-double en route to all-tournament honors for the second year in a row.

As a senior he averaged 16.1 points and 12.5 rebounds and he currently ranks 38th in Cincinnati career scoring (1,124 points) and 12th in rebounding (888). Then Wilson had a roundabout way to Olympic glory and one of the biggest thrills of his life. He originally wasn’t chosen to try out but his 19-rebound game for an AAU team in the Olympic trials led to his inclusion on the team going to Tokyo. Wilson had some key baskets in the final minutes of a close win over Yugoslavia in the U.S. team’s fifth game and it rolled from there to a 9-0 finish and Gold medal.

"When they put those gold medals around our necks, I don't know how I could have had a bigger smile," Wilson said in an October 2020 story in Cincinnati’s UC Magazine. "I think I cracked the corners of my mouth smiling so big. I was like a little kid at Christmas.

"The Olympic experience is the greatest thing ever. There is nothing like it."

Wilson was a territorial pick of the Cincinnati Royals and started his NBA career playing alongside Robertson in 1964. He stayed in the league until 1971 and averaged 5.4 points and 5.2 rebounds in 410 games with the Royals, Bulls, Seattle Supersonics, Phoenix Suns, Philadelphia 76ers and Buffalo Braves.

Wilson came home early in the Bulls’ 1966-67 expansion season in a trade for Lenny Chappell. He played 43 games and averaged 4.6 points and 3.8 rebounds in only 10 minutes an outing as Johnny “Red” Kerr’s team was swept in the playoffs in 3 games by the St. Louis Hawks. His best season was in 1968-69 when he averaged 8.8 points and 9.1 rebounds while splitting the season between the Suns and Sixers.

After his career ended, he remained in Cincinnati and became a youth advocate, teacher of at-risk students and motivational speaker, according to UC Magazine. The Cincinnati Enquirer story on Wilson’s death said he was still a presence at Bearcats’ games and enjoyed meeting the team’s players.

Wilson was a charter member of the Illinois Basketball Coaches Association (IBCA) Hall of Fame in 1973 and is also a member of the University of Cincinnati, Ohio basketball and Northern Kentucky halls of fame.

“George was looked upon as a messiah,” Pitts told Taylor Bell for his book. “No one used that language at that time, but everyone knew he was so good that when he linked up with other talent the West Side’s ambition to be the best in basketball was going to come to fruition.”

Wilson and Marshall opened the door for the Chicago Public League to become a power in Illinois high school basketball.

“It is more meaningful now because when I was doing it at the time I was just having fun, going to school, working, playing basketball and planning to go to college,” Wilson told Bell. “Years later, I realize it was a great feat in the 1950s with the race climate being what it was. It makes me feel good that I didn’t let anyone down.”

And that’s why George Wilson ranks up with the legends of Illinois and Chicago basketball.