Fun and games weren’t on the schedule for Len Rohde when he walked into Palatine High School as a freshman 70 years ago.

The big ol’ farm boy figured when the school day was done his work was just beginning. There were chores to help his dad and family with on their land on Algonquin Road, where St. Michael’s Cemetery now sits just across from the Harper College campus.

Palatine football coach Charlie Feutz saw the 6-foot-1, 200-pound kid and wondered why he wasn’t in shoulder pads and a helmet.

“I kept trying to talk him into it and he’d turn about 10 shades of red,” Feutz, who became the longtime athletic director at Conant, told reporter Larry Everhart in 1971.

“I do remember walking into that classroom on my first day in high school and how Charlie looked at me and said he’d see me after class,” Rohde said before his 2000 Palatine Hall of Fame induction to Daily Herald prep guru Bob Frisk. “I was pretty big, relative to the other kids at the time, and I guess they saw some hope for the big hayseed guy.”

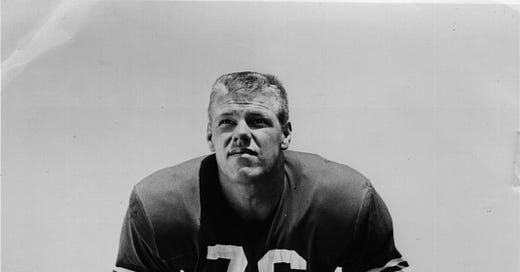

Coaches like Feutz and John Ellis saw someone who would become one of the greatest athletes in Palatine and northwest suburban history. Rohde went from the self-described big hayseed to a long and distinguished career as an NFL offensive lineman who still shares the San Francisco 49ers record for consecutive games played at 208.

Rohde, who passed away May 13, 2017 at 79, was more of a quick study than a late bloomer.

Right after he started playing football as a sophomore he became a varsity starter. As a a junior he was on one of the best teams in the school’s early era that finished 7-1 and second in the Northwest Conference. In his two years of wrestling he finished third in the state at heavyweight and became Palatine’s first state champion in the sport as a senior. In track and field he was the first in school history to hit 50 feet in the shot put.

“Those early sports memories at Palatine are still the best,” Rohde told Frisk in 1979. “Playing football for Charlie Feutz and wrestling for John Ellis. They are such class people, real gentlemen.”

Rohde also credited friends like George Sailor, Bob Kolze, Ormal Prust, Jim McCreery and Dave Abrahamson for helping convince him to spend more time plowing over opposing players instead of the family fields. Feutz needed only one game to insert Rohde in the starting lineup.

“It took Charlie two years to teach the farm boy, who had never seen a football before, the difference between offense and defense,” Rohde told Frisk.

His wrestling exploits were remarkable. In Rohde’s first match, Feutz said he “picked up a heavy kid and set him down on the mat for a pin. That poor kid’s mouth was hanging open.”

In his first six matches, Rohde beat third- and fourth-place state finishers from a year earlier en route to becoming Palatine’s first state wrestling place-winner. As a senior, Rohde didn’t lose in 26 matches and set a school record for pins in a season (17) that stood for 24 years. In four state tourney matches he outscored his opponents 32-3, which included an 11-3 semifinal rout of New Trier’s Mike Pyle, who was the Bears starting center from 1961-69.

“The college and NFL days were great, but winning that state wrestling heavyweight championship for Palatine ranks as one of the real high points,” Rohde told Frisk. “It has to be like winning a gold medal.”

Rohde credited Ellis for getting a scholarship to Utah State and he quickly transitioned to focus on football. Rohde was an all-conference tackle in his final two seasons and his play was celebrated with his induction into the Utah State Hall of Fame in 1995 and a spot on the school’s all-century team.

He was taken in the fifth round of the 1960 NFL Draft by the 49ers. He didn’t plan on staying on the West Coast too long with future Hall of Famers and characters Leo Nomellini and Bob St. Clair in the way.

“I didn’t think I was much of a pro prospect,” Rohde told Frisk shortly after he retired before the start of the 1975 season. “I really didn’t know too much about the 49ers when I was drafted.

“I got a booklet and started reading about people like Bob St. Clair and Leo Nomellini, who were wrestling bears and eating raw meat. And I figured, well, it will be a nice trip to California and back. But I didn’t want to go away without at least giving it a shot.”

Rohde, who grew to 6-4, 250 pounds, showed enough to stick around as he alternated between the offensive and defensive lines in his early NFL years. He moved in as the starting right tackle late in the 1962 season when St. Clair tore his Achilles. One of his biggest thrills was the 2-win 49ers handing the 1963 NFL champion Bears their only loss.

He became the starting left tackle in 1964 and established himself as one of the NFL’s best offensive linemen. In 1970, he was part of a group that allowed quarterback John Brodie to only be sacked an NFL-record 8 times. He played in the Pro Bowl in 1971 and helped the 49ers reach two consecutive NFC championship games.

“He is so good I have to go over the films two or three times before I find any mistakes,” 49ers offensive line coach Ernie Zwahlen told Everhart. “I wish I had five like him.”

But after the 1974 season, Rohde was battling some back trouble and head coach Dick Nolan suggested it was time to retire. Only the Raiders’ Jim Otto and George Blanda had played more consecutive games professionally at that point than Rohde’s 208, a team record equaled by long snapper Brian Jennings (2000-12).

“I was exceptionally lucky I was able to play every game,” Rohde told the Daily Herald’s Mark Ruda in 1995. “Sure, I had some injuries, but I’ve never been under the knife. Friends of mine, other players, I’ve seen numerous injuries that have cut short careers.”

Rohde originally thought he wanted to go into coaching but didn’t like the constant instability. Instead, he became a successful businessman who owned and operated a number of Burger King and Applebee’s restaurants in the Bay Area.

But Rohde never forgot his roots and those who helped him get his start at Palatine. Even if the old family farm, where he once thought his after-school time would be better spent, was nearly unrecognizable.

“It’s like dropping in on Mars,” Rohde told Ruda.